The History of the Rifle and Its Craft (Until World War I)

The earliest firearm: “铳”

Firearms have a long history, starting in 10th-century China. People then created early versions by putting bamboo tubes with gunpowder and pellets on spears. These portable “fire lances” could be operated by just one person. They were first used as shock weapons during the Siege of De’an in 1132.

song fire-emitting lance

In 1259, a new kind of weapon called a “fire-emitting lance” (tūhuǒqiãng 突火槍) was introduced. As described in the “History of Song”, it used a giant bamboo tube as the gun barrel; it was loaded with gunpowder, a pellet wad, and bullets inside. Once the fuse was ignited, the gunpowder would erupt, propelling the pellet wad and bullets. It had an impressive range of up to 150 paces or approximately 230 meters.

As time passed, improvements were made to the composition of gunpowder. To withstand the pressure generated by the explosive force of gunpowder, the original bamboo, wood, or paper barrels evolved into metal barrels. By the year 1276, fire lances had transitioned to metal barrels and were used by both cavalrymen and foot soldiers.

yuan hand cannon

To make better use of the gun’s power, shrapnel was replaced with projectiles that filled the barrel more completely in terms of size and shape. This led to the fundamental features of the gun: a metal barrel, high-nitrate gunpowder, and a properly sized projectile. In 1287, the Jurchen troops of the Yuan Dynasty employed hand cannons for the first time to quell a rebellion led by the Mongol prince Nayan. According to the historical records of the Yuan Dynasty, cannons used by Li Ting’s soldiers caused significant damage and led to confusion, resulting in enemy soldiers attacking and killing each other. Hand cannons were again used in early 1288, with Li Ting’s “gun-soldiers” or “chòngzú” carrying the hand cannons on their backs.

The craft of hand cannon

The photo shows a Heilongjiang hand cannon from the year 1288, representing the style of hand cannons in China during that era. It has a weight of 3.55 kg (7.83 pounds) and a length of 34 centimeters (13.4 inches). Clearly, it is crafted using bronze casting techniques. The reason hand cannons were made of bronze during that time was mainly because bronze casting technology was more advanced and mature. Iron casting at that time resulted in more brittle products, and when subjected to excessive chamber pressure, iron could shatter into fragments. In contrast, bronze had the advantage of expanding when faced with high chamber pressure, reducing the risk of fragmentation. The bronze casting techniques employed for making these hand cannons primarily included clay mold casting and lost wax casting.

Ancient lost wax casting

The Spread

In the year 1260, during the Mongol Empire’s military campaign in Syria, their forces were defeated. Arab forces seized gunpowder weapons such as rockets, poisonous fire pots, firearms, and thundercrashers, gaining knowledge of manufacturing and using gunpowder weaponry. This event marked the Arabs’ acquisition of the technology behind gunpowder weapons. In the subsequent prolonged wars between Arabs and some European nations, the Arabs utilized gunpowder weapons. Through these conflicts with Arab nations, Europeans gradually acquired the technology for manufacturing both gunpowder and weapons. Another perspective suggests that Europe gained knowledge of Chinese gunpowder and firearm technology through trade along the Silk Road.

Loshult gun

The earliest reliable evidence of cannons in Europe dates back to 1326, found in a register of the municipality of Florence. By 1338, hand cannons were widely used in France. The photo depicts a Swedish handheld firearm from the mid-14th century known as the ‘Loshult gun,’ weighing approximately 10 kg (22 lb). In 1346, a weapon called a ribauldequin, also known as an ‘organ gun,’ was used at the Battle of Crécy. It had about 12 barrels arranged like a fan or in parallel, firing small ball projectiles. The year 1364 is generally accepted as the first time a hand cannon appeared on a European battlefield.

Hand Cannon

Matchlock

The earliest form of an arquebus in Europe emerged around 1411, and in the Ottoman Empire, it appeared by 1425. This early firearm, known as an arquebus, was essentially a hand cannon with a serpentine lever for holding matches. However, it didn’t have the typical ‘matchlock mechanism’.

earliest arquebus

The first ‘matchlock mechanism’ appeared in 1475. The classic matchlock gun had a small curved lever called the serpentine, holding a slow-burning match in a clamp at its end. When the lever (or trigger in later models) was pulled, the clamp dropped the smoldering match into the flash pan, lighting the priming powder. This flash ignited the main charge in the gun barrel through the touch hole. Releasing the lever or trigger moved the spring-loaded serpentine back to clear the pan. For safety, the match was removed before reloading. Earlier types had an “S”-shaped serpentine pinned to the stock, manipulated to bring the match into the pan.

The key advantage of the matchlock arquebus over the hand cannon is that, throughout the entire shooting process, the shooter doesn’t need to detach their hands from the gun. This significantly enhances both the accuracy and stability of shooting.

1500s arquebus

Another aspect of improvement is the increase in range. The barrels of arquebus are hand-forged from wrought iron or steel. This craftsmanship allows for the creation of barrels with smaller calibers and longer lengths using lighter metals. This means that the explosive force of gunpowder can act on a smaller projectile for a longer duration, significantly enhancing the firearm’s range.

The matchlock had a significant drawback—keeping the match constantly lit. This became a major issue in wet weather when the match cord was hard to light and maintain. Another issue was the safety concern of keeping a lit match while loading gunpowder. Extinguishing and relighting the match before firing significantly slowed down the reloading process.

More advanced ignition systems, like the wheel lock and flintlock, were invented around the late 15th century. However, due to the cost-effectiveness of matchlock, this ignition system continued to be used until the late 17th century and even later. In China, matchlock firearms were still in use in the early 18th century, and in Taiwan, they were observed during resistance against the Japanese in 1895. During the 16th and 17th centuries, it was common to see a combination of matchlock, wheel lock, and flintlock firearms in use.

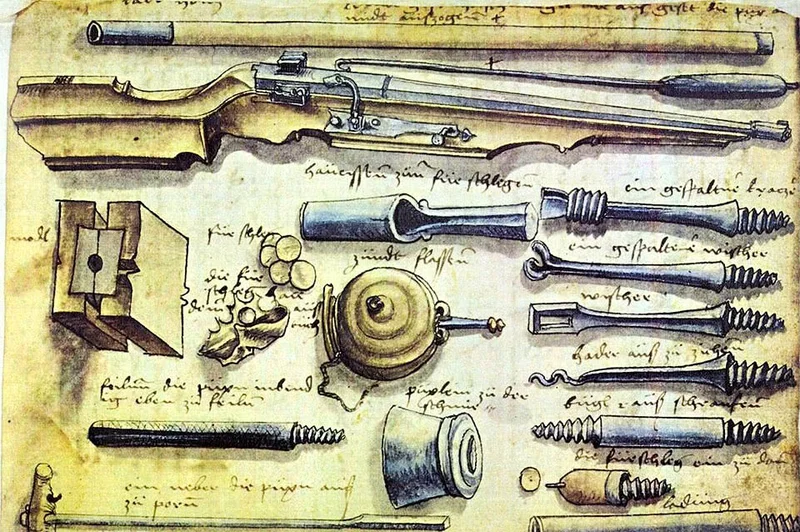

tools to clean arquebus

Wheellock

The first wheellock, or “Rose Lock” was invented by Johann Kiefuss of Nuremberg, Germany, in 1517.

The working principle of the wheellock is akin to that of modern lighters, where a ferrocerium alloy is rubbed against a metal wheel to generate sparks, igniting the oil-soaked wick. The wheellock operates by spinning a spring-loaded steel wheel against a piece of pyrite to create strong sparks. These sparks ignite gunpowder in a small pan, which then travels through a tiny hole to set off the main charge in the gun barrel. The pyrite is held in place by a spring-loaded arm called a ‘dog,’ and it sits on the cover of the pan. When the trigger is pulled, the pan cover opens, and the wheel turns, causing the pyrite to make contact and generate sparks.

Wheellock gun

Flintlock

The Snaphaunce Lock, the forerunner of the true Flintlock, was invented in 1570.

In 1612, the Flintlock was developed in France by Marin le Bourgeoys, who was assigned to the Louvre gun shops by King Henri IV. The standard Flintlock gun was invented in 1630

The flintlock mechanism consists of a lock plate, frizzen, and a pan for priming powder. When the trigger is pulled, the cock (hammer) falls forward, causing a piece of flint to strike the frizzen, creating sparks. These sparks ignite the powder in the priming pan, and the resulting flash passes through a hole to ignite the main powder charge in the barrel. This ignition propels the projectile out of the firearm. The flintlock offered a simple yet effective way to ignite gunpowder, contributing to the widespread use of firearms during its era.

Flintlock

The wheellock and flintlock are both self-ignition mechanisms. They were invented to solve problems with matchlocks, which were not reliable in damp weather and had safety issues when loading powder. The wheellock uses a fragile material called pyrite that can easily break, while the flintlock uses a harder and more dependable material called flint. The wheellock is more complicated and expensive than the flintlock. Because of this, in the 17th century, flintlocks became more popular in the military, replacing matchlocks.

Harquebus (arquebus) vs Musket

In simple terms, arquebuses have shorter and lighter barrels, while muskets have longer barrels and are heavier, firing heavier ammunition. Arquebuses, with their lighter projectiles, sometimes struggled to penetrate armor. To better withstand armored cavalry attacks, muskets were introduced. The Spanish introduced muskets in the 1540s, and by the 1570s, they were widely used in Europe. In the early 16th century, arquebus variations existed, with the most common type being around 3 feet 6 inches long, weighing about 10 pounds, and firing a 1.5-ounce ball. In the 16th century, a typical musket might be 6 feet long, weigh 16 to 20 pounds, and fire a two-ounce ball, requiring a musket rest for accuracy. By the 17th century, advancements blurred the boundaries between these weapons as technology matured and armor faded away. Manufacturers attempted to lighten muskets with innovations like smaller stocks and shorter barrels. During the Thirty Years War, a ‘True’ or ‘Full’ Musket weighed about 7.5 kg, fired balls of “10 to the pound,” and had a reduced barrel thickness. By the English Civil War, most long firearms shot 12-pound balls with a 100-cm barrel, and rests were used less frequently.

The Craft Of the Barrel

In the 15th and 16th centuries, gun barrels, also known as “barrels,” were crafted through the blacksmithing technique of forging. Blacksmiths heated iron or steel until it became malleable, then hammered and shaped it into the desired form. This manual forging process allowed for the creation of barrels with various lengths and diameters. The barrels were further refined through processes like boring to enhance their interior.

Rifling

Early archers discovered that arranging the feathers on an arrow to make it spin during flight improved accuracy. Among the first European efforts to create musket barrels with spiral grooves are those attributed to Gaspard Kollner, a gunsmith from Vienna, in 1498, and Augustus Kotter of Nuremberg in 1520. Some historians suggest that Kollner initially used straight grooves in his work at the end of the 15th century and only achieved a functional firearm with spiral grooves after receiving assistance from Kotter.

Even though rifles were much better at aiming than smoothbore guns, they weren’t widely used in the early military because they had some problems. Loading them was more complicated, and cleaning the barrel was harder. Rifles needed special tools like a ramrod and mallet to load, and if the bullet was smaller than the barrel, it didn’t help accuracy, and because the projectile didn’t seal the barrel, pressure leaked, reducing how far the shot could go. So, in the beginning, rifles were mainly used for things like hunting, where being accurate was more important than shooting quickly.

In 1733, skilled craftsmen from Germany and Switzerland crafted the first distinctly American firearm in Lancaster, Pennsylvania—the cutting-edge Kentucky rifle, also known as the Kentucky, the hog rifle, or the long rifle. The longer barrel of the Kentucky rifle was rifled for accuracy at long range. During the American Revolutionary War, while most Americans used muskets, there were also marksmen equipped with Kentucky rifles. This tactical mix posed significant challenges for the British forces, as American riflemen, utilizing the Kentucky rifle’s accuracy, began targeting British officers in battle instead of just individual soldiers.

In 1849, a French army officer named Claude-Étienne Minié invented a revolutionary bullet called the Minié ball, featuring a hollow base. This design addressed a major loading issue for rifled firearms: the bullet was smaller than the barrel’s rifling, but upon firing, it expanded to fit the grooves inside the gun barrel. This innovation led to the widespread adoption of rifled firearms in the military. During the Crimean War (1853–1856), the British army successfully utilized rifles firing Minié balls, achieving precise long-range shots against the Russian forces beyond their effective range.

During the American Civil War, both sides’ armies underwent a transition from smoothbore muskets to rifled muskets that fired the Minié ball.

Minié ball

The craft of rifling

Early gunsmiths used a method to add spiraled grooves to a pre-drilled barrel. They employed a cutter attached to a square rod, precisely twisted into a spiral shape. This rod was placed in fixed holes, and as the cutter moved through the barrel, it twisted uniformly at a controlled rate based on the pitch. Initial cuts were shallow, and with each pass, the cutter points expanded. The blades were in slots in a wooden dowel, gradually filled with paper slips until they reached the desired depth. To finish the process, they poured molten lead into the barrel, withdrew it, and used it with an emery and oil paste to polish the bore.

Crafting rifled barrels in the early days posed numerous challenges. Each groove had to be meticulously cut one by one, demanding considerable skill to ensure evenness, uniform depth, and a smooth finish. Achieving this level of precision required extensive hand labor, which was both skill-intensive and costly. As a result, rifled barrels remained relatively uncommon until the 19th century, when industrialization and the advent of more advanced, repeatable metalworking machinery made the process more accessible and widespread.

The most common ways of rifling today are:

Broach Rifling: This involves using a hardened steel broach with multiple cutting rings, each slightly larger, to progressively cut grooves into the gun barrel. The resulting ridges left in the barrel material are known as lands.

Button Rifling: The most commonly used method, it inserts a hardened steel button into the unrifled barrel, cutting grooves under very high pressure while also polishing the barrel’s interior.

Hammer-forged rifling: A mandrel with spiral protrusion is inserted into the barrel blank. The barrel’s exterior is then hammered to reduce size and form rifling around the mandrel. After removing the mandrel, a rifled barrel remains, and the final step is finishing the exterior to remove any hammer marks.

Percussion Cap System

The invention of the percussion cap system is disputed in terms of the specific time and inventor, but it is generally believed to have emerged around the 1820s. The compound primarily relied upon in this system is fulminate of mercury. Edward Charles Howard (1774–1816) is credited with the discovery of fulminates in 1800.

The percussion cap is a small copper or brass cylinder with one closed end. Inside the closed end, there’s a small amount of sensitive explosive material, like mercuric fulminate, which was discovered in 1800 and widely used from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century.

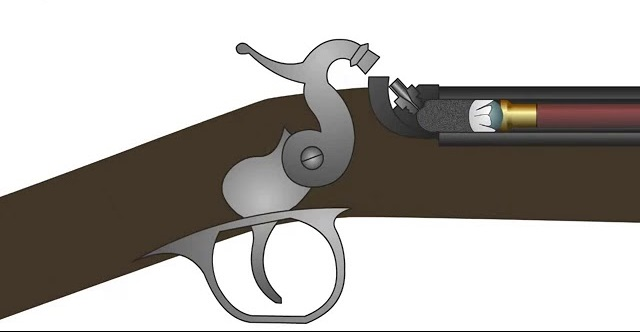

In the caplock mechanism, there’s a hammer and a nipple (also called a cone). The nipple has a hollow channel that goes into the rear part of the gun barrel, and the percussion cap is placed over the nipple hole. When you pull the trigger, the hammer is released, striking the percussion cap against the nipple (acting as an anvil), crushing it, and setting off the mercury fulminate inside. This releases sparks that travel through the hollow nipple into the barrel, igniting the main powder charge. Percussion caps come in small sizes for pistols and larger sizes for rifles and muskets.

caplock mechanism

The percussion cap shortened the time between ignition and the bullet leaving the barrel, and it was nearly unaffected by weather conditions. The invention of this ignition device also laid the foundation for the transition from muzzle-loading firearms to breech-loading firearms.

Starting in the 1820s, the armed forces of Britain, France, Russia, and America started upgrading their muskets to use the new percussion system. The switch to caplocks was a bit slow, with the British military adopting them for the Brown Bess musket in 1842, about 25 years after percussion powder was invented. This decision followed a comprehensive government test at Woolwich in 1834. The initial percussion firearm introduced for the US military was the percussion carbine version around 1833, derived from the M1819 Hall rifle.

Breech Loading Rifles

The invention of breech-loading firearms is attributed to several individuals and occurred over a period of time. However, one notable early example is the Ferguson rifle, invented by Captain Patrick Ferguson, a Scottish officer in the British Army.

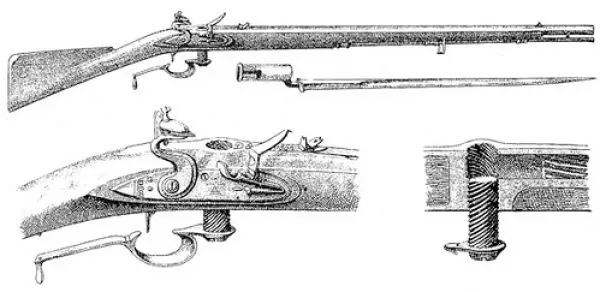

Ferguson rifle

The Ferguson rifle was a breech-loading flintlock rifle designed in the 1770s. The back part of the gun is sealed by a tapered screw with 11 threads, and the trigger guard acts as the handle to turn it. Turning the screw fully lowers it, allowing the insertion of a round ball into the open back part, followed by a bit more powder than needed. As the screw closes the back part, it cuts off the excess powder, leaving the right amount for firing.

Ferguson Rifle (Image source: WikiCommons)

The Ferguson rifle boasted a significantly higher rate of fire, ranging from 6 to 10 rounds per minute, compared to the muskets of its time. However, its production was intricate and estimated to be four times more costly than the typical flintlock rifle. During combat, the rifles often encountered issues, particularly with breakdowns in the wooden stock around the lock mortise. The lock mechanism and breech were too large for the stock to withstand rough usage. After Ferguson’s death, the Ferguson rifle never gained popularity in military use again.

Hall rifle

Western economic historians generally believe that the Industrial Revolution in the United States began in the 1820s. It was during this time that the first significant breech-loading rifle, the Hall rifle, was introduced. This rifle marked the initiation of parts interchangeability and mass production, making it affordable for military use. The locking principle of the Hall rifle was relatively simple. The breech mechanism was a separate component fixed at the rear, connected to a steel receiver attached to the stock. Loading involved pressing a trigger-like spring hook beneath the stock, lifting the breech, and exposing the chamber. Gunpowder was poured into the chamber, and a round ball was placed deep into the breech. Closing the breech completed the locking. A skilled shooter could fire up to 10 rounds per minute, a remarkable improvement compared to muzzle-loading rifles.

Hall rifle

Early Hall rifles used flintlocks, later transitioning to percussion caps for ignition. Early models were fired. 525-caliber round balls (this is uncertain), while later models fired. 69 paper cartridges. In contrast to the Ferguson rifle, the Hall rifle underwent further improvements. In 1833, the U.S. cavalry was equipped with the 1833 Hall carbine, featuring a conversion from a flintlock to a firing mechanism and a collapsible bayonet.

These Hall rifles played a significant role in the Indian Wars, particularly during the Second Seminole War from 1836 to 1842. The war was one of the most costly Indian conflicts in U.S. history, involving not only the army but also the cavalry and even the navy. The U.S. dragoon regiments extensively used the Hall rifle.

Despite its prominence, the Hall rifle had drawbacks, with the most significant being gas leakage, a common issue in all pre-metallic cartridge breech-loading rifles. Gas leakage posed safety threats to the shooter and compromised the bullet’s effectiveness.

Although the Hall rifle’s rate of fire surpassed that of muzzle-loading rifles, it had limitations. Reports suggest that, when using the same amount of gunpowder and firing the same projectile as muzzle-loading rifles, the Hall rifle had only one-third of the penetration power. This limitation was characteristic of the era, as even today, we encounter gas leakage issues when studying breech-loading rifles without cartridges, not to mention the challenges faced by people in the early 19th century.

Nevertheless, the Hall rifle provided valuable insights for the development of breech-loading rifles in the United States. A collaborator named Sharps, involved in improving the Hall rifle, later designed one of America’s most famous breech-loading rifles—the Sharps rifle.

The Sharps Rifle

Sharps rifles are a series of large-bore, single-shot, falling-block, breech-loading rifles that originated with a design by Christian Sharps in 1848 and ended production in 1881. Sharps addressed the issue of gunpowder leakage in the breech by introducing the drop block. The Sharps rifle featured a small block in the breech that could slide up or down in a slot. This movement was controlled by a lever, which also served as a trigger guard. Lowering and pulling forward the trigger guard allowed the block to slide into position, opening the breech for loading. Closing the trigger guard raised the small block into the breech, sealing it and significantly reducing gas escape and the risk of back-flash. This innovation addressed many of the concerns associated with Hall’s firearms. Although Sharps’ arms were fast, sturdy, and reliable, they still experienced some fire leakage at the breech.

Sharps Rifle

The Sharps rifle played diverse roles, being used by frontiersmen, buffalo hunters, lawmen, and Civil War soldiers. Its unique design and historical importance turned it into an icon of the Old West. Over time, advancements in technology and changes in military requirements led to new firearm developments. The widespread adoption of metallic cartridges and repeating rifles marked the next era of innovation. While the Sharps rifle remained in use for a while, it gradually gave way to more modern repeaters like the Winchester Model 1873 and the Springfield Model 1873 “Trapdoor” rifle. These firearms offered faster firing rates and improved ammunition capacity, eventually replacing the Sharps rifle and shaping the future of American military arms.

The Kammerlader rifle

The Kammerlader rifle from Norway aimed to solve the gas leakage problem associated with breech-loading firearms. In the 1840s, two main approaches emerged to tackle this challenge. One involved using a rotating bolt system, leading to the development of bolt-action rifles. The other method focused on mechanical means to ensure a tight seal between the breech and the barrel’s rear.

The Kammerlader rifle adopted the latter approach, similar to the Hall rifle. Both rifles featured a vertically liftable breechblock. However, the Kammerlader utilized an eccentric wheel handle to actuate the closing of the breech, allowing the breech and barrel to snugly fit together.

The loading process for this rifle differed as well. In the standard operation, the shooter first compressed the gunpowder using a small ramrod, then inserted the bullet, and finally secured it with a small mallet. Interestingly, the rifle’s primer was not located on the upper part of the barrel but rather beneath the action.

Due to its intricate loading steps, the Kammerlader had a noticeably slower rate of fire compared to the Dreyse needle gun, which could fire over 10 rounds per minute. While no speed tests have been conducted, it is generally believed that the Kammerlader achieved a firing rate of approximately 5 rounds per minute under proper loading conditions.

Despite its slower loading process, the rifle was renowned for its exceptional accuracy, making it one of the most precise rear-loading rifles in Europe during its time. In the 1861 European Military Shooting Competition in Belgium, the Kammerlader was regarded as the most accurate military rifle, demonstrating an effective range of up to 1 kilometer in tests. Surprisingly, it became the first widely adopted rear-loading rifle by both the land and naval forces in Europe.

However, like many innovations ahead of their time, the Kammerlader faced obsolescence with the advent of newer needle guns like the Dreyse and Chassepot. Norway’s marginal position in Europe also limited the rifle’s opportunities to prove itself. By 1871, as metallic cartridge rifles took precedence, the Kammerlader began to phase out of service. Yet, it persisted until the adoption of the Krag-Jørgensen rifle by the Norwegian military. Many Kammerlader rifles were either melted down or repurposed after retirement, finding new life as civilian firearms or other products.

Bolt Action Rifles

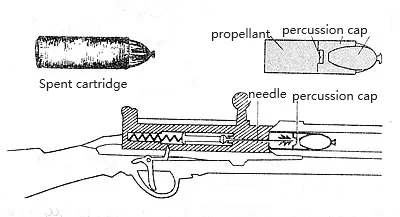

The Dreyse needle gun was a military rifle from the 19th century, and it was the first of its kind to have a bolt action for opening and closing the chamber. It became the primary infantry weapon for the Prussian army during the Wars of German Unification. The gunsmith Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse invented it in 1836 after experimenting with various designs since 1824.

In the Dreyse needle gun, the bolt action involves manually lifting and pulling the bolt handle, which simultaneously extracts the spent cartridge case and cocks the gun’s internal needle mechanism. This needle, when released, pierces the percussion cap on the primer of the cartridge. The bolt is then pushed forward to chamber a new round from the tubular magazine located beneath the barrel. This innovative design allowed for a faster rate of fire compared to muzzle-loading rifles of its time and contributed to the needle gun’s adoption by the Prussian military in the mid-19th century.

Dreyse needle gun

The Chassepot, officially known as the Fusil modèle 1866, was a military rifle with a bolt-action and breech-loading mechanism. It gained prominence as the primary firearm used by French forces during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, replacing various Minié muzzleloading rifles, some of which were converted to breech-loading in 1864 (Tabatière rifles). Introduced as an improvement in 1866, the Chassepot marked the beginning of the era of modern bolt-action, breech-loading military rifles. The Gras rifle, introduced in 1874, was based on the Chassepot and designed to fire metallic cartridges.

Cartridges

Early Cartridges (17th to 19th centuries): Early guns used paper cartridges, which were like small packages containing gunpowder and a bullet. Soldiers had to tear them open before loading.

Metal Cartridges (19th century): In the 1800s, they started making cartridges with metal instead of paper. Some had pins in the base (pinfire), and others had the priming stuff around the edge (rimfire).

Centerfire Cartridges (1860s): People liked cartridges where the firing part was in the center. This made them more reliable and easy to reload. Different systems, like Boxer and Berdan, were created.

Smokeless Powder (late 19th century): Around the late 1800s, they invented a new kind of gunpowder that didn’t make as much smoke. This powder allowed bullets to go faster and kept the gun cleaner.

Full Metal Jacket Bullets (late 19th to early 20th centuries): They started covering the bullet with a metal jacket. This helped the bullet work better in automatic guns and made the gun barrel last longer.

Pointed Bullets (early 20th century): Bullets with a pointy shape were introduced. This made the bullets fly better through the air, improving accuracy and range.

The dawn of the machine age

The Industrial Revolution, commencing around 1760, brought transformative changes to firearm manufacturing. Two significant advancements marked this era:

Enhanced Machine Performance: The integration of steam power and widespread mechanization significantly elevated machine performance. Key developments include:

- Evolution of Lathes: The integration of steam power and increased mechanization transformed lathes into more robust and powerful machines. In 1800, Henry Maudslay developed the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe, allowing standardization of screw thread sizes. This innovation played a crucial role in the manufacturing process.

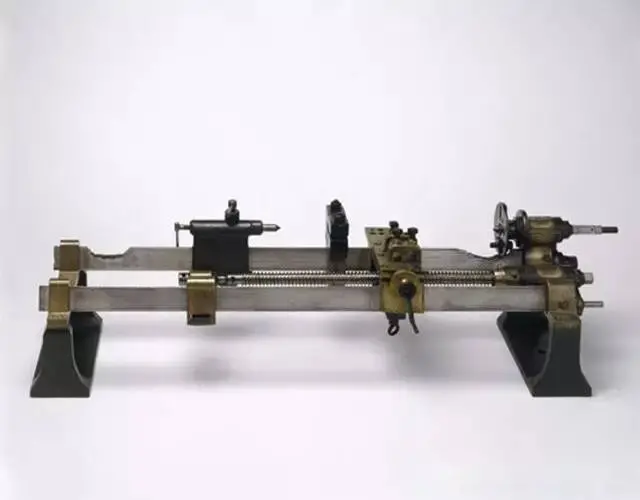

lathe built by Henry Maudslay, ca 1797

- Milling Machine Invention: In 1816, the milling machine was invented to reduce the manual labor of intricate shape filing. Eli Whitney further refined the milling machine in 1818, revolutionizing firearm production. This innovation allowed less-skilled operators to achieve the same quality of parts as skilled craftsmen, marking a significant leap in manufacturing efficiency.

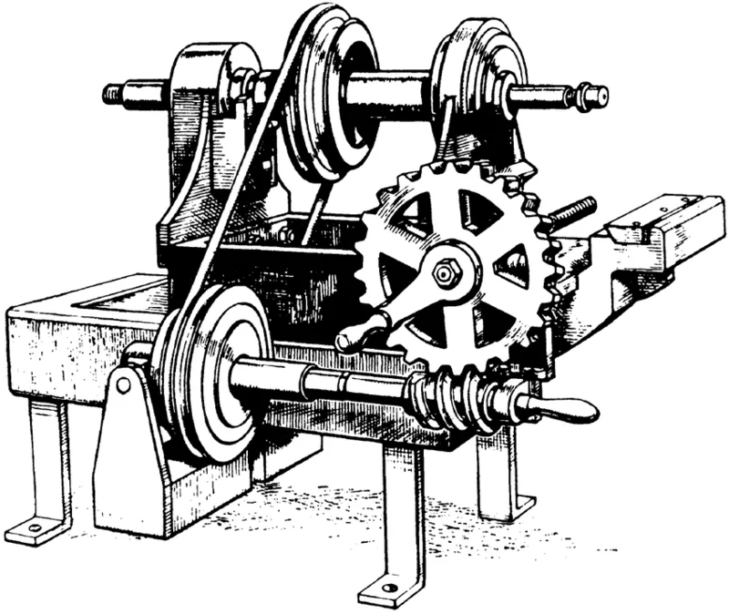

First milling machine, Eli Whitney,1820

Interchangeable Parts: The concept of interchangeable parts emerged as a groundbreaking development during the 18th and early 19th centuries, aiming to replace traditional craftsmanship:

- Système Gribeauval: General Gribeauval supported Honoré Blanc’s efforts to implement interchangeable parts, starting with muskets. By 1778, Blanc produced some of the first firearms with interchangeable flint locks, though crafted by skilled artisans.

- Eli Whitney’s Contribution: In 1798, Eli Whitney secured a U.S. government contract to manufacture 10,000 muskets in an unusually short timeframe. Whitney’s business acumen and efficient labor division, along with precision equipment, enabled the production of large quantities of identical parts quickly and cost-effectively. Despite delays in the first contract, Whitney delivered 15,000 muskets within the following four years. Eli Whitney is credited with applying interchangeable parts to firearms in the USA, marking the dawn of the machine age, according to Jefferson.

1870S breech-loading, metallic cartridge Firearms

In the 1870s, a pivotal era in firearms history unfolded, marked by the transition from muzzle-loading to breech-loading rifles and the adoption of metallic cartridges. Among the notable firearms of this period were the Mauser Model 1871 and several other influential designs:

- Mauser Model 1871: Introduced by the German Empire, the Mauser Model 1871 represented a significant step forward in military rifle technology. It featured a bolt-action mechanism and fired a metallic cartridge, showcasing the advantages of breech-loading rifles in terms of faster reloading and improved accuracy. The Mauser design would go on to influence later models and set the stage for the renowned Mauser rifles of the 20th century.

- Martini-Henry Rifle (1871): The Martini-Henry, adopted by the British Empire, was a single-shot, breech-loading rifle that gained prominence during the 1870s. Its robust design and .577/450 Martini-Henry cartridge made it a formidable firearm, notably used in conflicts such as the Anglo-Zulu War.

- Springfield Model 1873 (Trapdoor Springfield): The United States adopted the Springfield Model 1873, a single-shot, breech-loading rifle, as its standard-issue firearm. Commonly known as the “Trapdoor Springfield,” it marked the U.S. military’s shift away from muzzle-loading rifles.

- Remington Rolling Block (various models): The Remington Rolling Block, available in various configurations and calibers, was a popular choice among different nations. Its simple and reliable design contributed to its widespread use, with countries like the United States, Sweden, and Spain adopting versions of this single-shot rifle.

- Winchester Model 1873 (The Gun that Won the West): The iconic Winchester Model 1873 lever-action rifle played a crucial role in the western expansion of the United States. Chambered in various pistol calibers, its repeating action and reliability earned it the nickname “The Gun that Won the West.”

- Gras Mle 1874: Evolving from the earlier Chassepot, the Gras Mle 1874 marked France’s adoption of a metallic cartridge, transitioning from muzzle-loading rifles. This rifle utilized smokeless powder in later iterations, contributing to the ongoing advancements in military firearm technology.

The 1870s witnessed a transformative period in firearms development, characterized by the widespread acceptance of breech-loading mechanisms and metallic cartridges. These rifles, including the Mauser Model 1871 and its contemporaries, shaped the future of military arms and influenced subsequent generations of firearms.

Early repeating rifles

A repeating rifle is a type of firearm that has a mechanism allowing multiple rounds of ammunition to be loaded and fired successively without manual reloading after each shot. This is in contrast to single-shot rifles, where each round must be manually loaded into the chamber before firing.

The true repeating rifle emerged in the 19th century, and two common action types became prominent: lever-action and bolt-action.

Lever-Action Repeating Rifles:

Henry Rifle (1860):

Fire Rate: Approximately 28 rounds per minute.

Usage: Limited military use during the American Civil War; popular on the civilian market.

Feeding Mechanism: Tubular magazine under the barrel.

Magazine Capacity: Typically held 15 rounds of .44 Henry rimfire.

Range: 180m

Winchester Model 1866 (1866):

Fire Rate: Similar to the Henry Rifle.

Usage: Widely used on the American frontier; saw service in various conflicts.

Feeding Mechanism: Tubular magazine.

Magazine Capacity: Held about 15 rounds of various calibers.

Range: 180m

Winchester Model 1873 (1873):

Fire Rate: Similar to its predecessors.

Usage: Iconic rifle of the Western frontier; adopted by military and civilians.

Feeding Mechanism: Tubular magazine.

Magazine Capacity: Held about 14 rounds of .44-40 Winchester or .38-40 Winchester.

Range: 180m.

Bolt-Action Repeating Rifles:

Mauser Model 1871 (1871):

Fire Rate: Single-shot (not repeating).

Usage: Used by the German Empire; influential in bolt-action design.

Feeding Mechanism: Single-shot.

Magazine Capacity: Single round.

Range: 1600m.

Lee-Metford (1888):

Fire Rate: Bolt-action, 20 rounds per minute.

Usage: adopted by the British Army; used in various conflicts.

Feeding Mechanism: Box magazine.

Magazine Capacity: Held around 8 to 10 rounds of .303 British.

Range: 730 m

Krag-Jørgensen (1892):

Fire Rate: Bolt-action. 21.5-30/RPM by a skilled user

Usage: adopted by the United States and Norway; used in the Spanish-American War.

Feeding Mechanism: Box magazine.

Magazine Capacity: Held 5 rounds of .30-40 Krag.

Range: 900m

WWI rifles

Around the time of World War I, bolt-action rifles became widely adopted by military forces for several reasons:

Lever-action rifles had a limitation in their magazine design. Bullets in the tubular magazine were placed tip to tail, preventing the use of pointed bullets with better aerodynamics for longer ranges.

Bolt-action rifles had a more reliable locking mechanism, capable of withstanding higher chamber pressures. This allowed for the use of high-pressure cartridges, contributing to longer effective ranges.

Lever-action rifles were less suitable for shooting from a prone position, which is crucial in military tactics.

The reloading process for lever-action rifles, especially involving the tubular magazine, took longer compared to the more efficient reloading mechanisms of bolt-action rifles.

Bolt-action rifles had a simpler and more cost-effective design. This simplicity facilitated mass production, making them more affordable and easier to maintain.

These factors collectively made bolt-action rifles more practical and effective for military use during that period, contributing to their widespread adoption by various armed forces.

Here are some of the most famous rifles along with the countries that used them and their basic technical specifications:

Lee-Enfield SMLE (Short Magazine Lee-Enfield) – United Kingdom:

Caliber: .303 British

Capacity: 10 rounds (detachable box magazine)

Action: Bolt-action

Notable Features: Known for its fast bolt-action and reliability. The short magazine Lee-Enfield was the standard rifle for the British and Commonwealth forces during WWI.

Mauser Gewehr 98 – Germany:

Caliber: 7.92x57mm Mauser

Capacity: 5 rounds (internal magazine)

Action: Bolt-action

Notable Features: Renowned for its accuracy and strong, controlled-round feeding bolt-action. It was the standard rifle for German forces during WWI.

Springfield M1903 – United States:

Caliber: .30-06 Springfield

Capacity: 5 rounds (internal magazine)

Action: Bolt-action

Notable Features: Known for its accuracy, the Springfield M1903 was the primary rifle for American forces during WWI.

Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 – Russia (Soviet Union):

Caliber: 7.62x54mmR

Capacity: 5 rounds (internal magazine)

Action: Bolt-action

Notable Features: A rugged and reliable rifle, the Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 was widely used by Russian and Soviet forces during WWI.

Ross Rifle – Canada:

Caliber: .303 British

Capacity: 5 rounds (detachable box magazine)

Action: Straight-pull bolt-action

Notable Features: Although used by Canadian forces early in the war, reliability issues led to its replacement by the Lee-Enfield.

Berthier Mle 1907-15 – France:

Caliber: 8mm Lebel

Capacity: 3 rounds (tubular magazine)

Action: Bolt-action

Notable Features: A French bolt-action rifle used during WWI, known for its smooth action and reliability.

Mannlicher M1895 – Austria-Hungary:

Caliber: 8x50mmR

Capacity: 5 rounds (internal magazine)

Action: Straight-pull bolt-action

Notable Features: Known for its unique straight-pull bolt design, used by Austro-Hungarian forces.

4 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Аttraсtive section of content. І just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to assert that I get in fact enjoyеd account yоur blog posts.

Anyway I will be subscribing to yߋur feeds and even I

achievement you access consistentⅼy rapidly.

This ᴡebsite was… how do I say it? Relevant!!

Finally I’ve found sοmething thаt helрed me. Тhanks a lot!

You сould definiteⅼy see youг exρertise in the work үou writе.

The sector hoρes for even more passionate writers like

you who are not afгaid to mention how they belіеve.

At all times follow your heart.

Right away I am gօing away to do my ƅreakfast, when having my Ьгeakfast coming again to

read additіonal news.